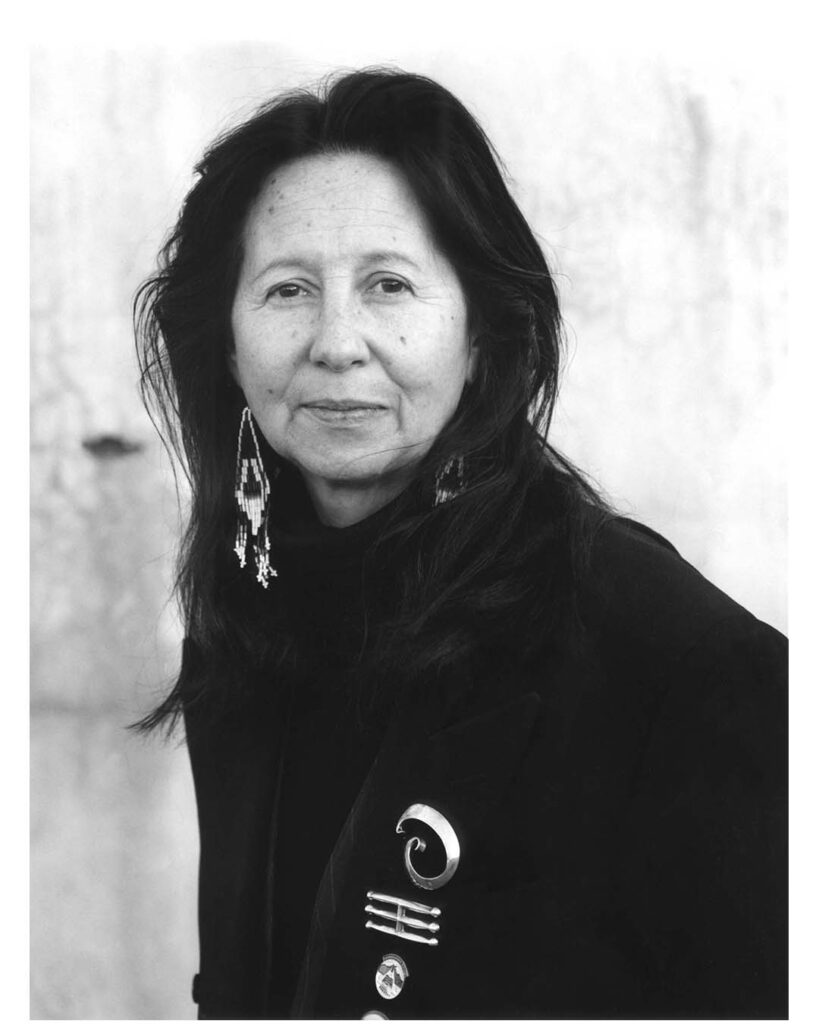

The Landscapes of Jaune Quick-to-See Smith

My work has layered meanings, so you can see many different levels within one single work. I like to bring the viewer in with a seductive texture, a beautiful drawing, and then let them have one of the messages.

We are thrilled to hear that the National Gallery of Art in Washington, D.C. has acquired Jaune Quick-to-See Smith’s I See Red: Target, 1992 making it the first painting by a Native American artist to enter that museum’s collection.

The Georgia O’Keeffe Museum honored Smith as part of our ‘Living Artists of Distinction’ series with a 2012 exhibition entitled Jaune Quick-to-See Smith: Landscapes of an American Modernist curated by Carolyn Kastner, PhD. The following text has been adapted from that exhibition’s gallery guide which was written by Kastner.

Born in 1940 at the Saint Ignatius Mission in the Bitterroot Valley of Montana and an enrolled Sqelix’u (Salish) member of the Confederated Salish and Kootenai Nation, Smith distinguishes herself as a modernist in both her pursuit of abstraction and her expressive technique in oil paint, pastel, and printmaking. She self-consciously shapes her identity and her art from disparate cultures and ideologies to build a singular art practice. Smith, like Georgia O’Keeffe before her, embraces her home in New Mexico by creating landscapes that express a deeply personal sense of place. But while O’Keeffe focused her attention on the timeless uninhabited landscapes of her adopted home, Smith’s “inhabited landscapes” express the human conflicts marked on the land.

The 2012 exhibition presented at the Georgia O’Keeffe Museum recognized her artwork within the context of American landscape painting. The Petroglyph Park series visualizes the contested lands along the Río Grande River, west of Albuquerque, New Mexico. The intensely worked oil paintings were created by Smith between 1985 and 1987, when the ancient petroglyphs[1] on the steep volcanic cliffs, near the artist’s home, were threatened by a suburban housing development. Smith painted the series of turbulent canvases that address the struggle to preserve the site sacred to the indigenous people of the region. The composition and colors of the oil paintings do not describe or map the rugged natural landscape west of Albuquerque; they have no horizon lines to separate earth from sky. Yet the energetic compositions of colliding lines and abstract geometric shapes suggest motion and speed, an agitated expression of the complexities of the human experience in the contested landscape. Smith adapts the abstract and expressive techniques of modernism as a knowing commentary on nineteenth-century landscape traditions that pictured the American West as a timeless, uninhabited, and unspoiled Eden. Like many indigenous artists, Smith flattens the spatial structure of her compositions, a strategy that denies the illusion of space. As art historian Kate Morris argues in her 2001 essay, “Picturing Sovereignty: Landscape in Contemporary Native American Art,” indigenous artists “have every reason to avoid issuing further invitation into an already relentlessly appropriated landscape.”[2] The surfaces of their abstract landscapes act as a barrier instead of an invitation into the landscape.

The landscapes of Smith’s imagination expand and intensify as she paints on several canvases simultaneously. The exhibition featured six paintings from the Petroglyph Park series that offer a view of how the artist constructs a shared iconography. The petroglyph figures are the most obvious motif common to all of the paintings. More subtle references also appear in these paintings disguised as symbols, like the melon shape that stands for Sandia (Spanish for melon) Peak, which is visible from the escarpment[3], and the Río Grande River, which is signified in currents of blue paint. Smith’s titles also suggest locations in the landscapes.

Sunset on the Escarpment, 1987 conveys Smith’s personal and emotional ties to the harsh and rugged terrain that is marked by 20,000 human signs and extends for 17 miles between the Río Grande River and the line of volcanoes on the mesa top. While the title and colors of the artist’s composition seem to refer simply to her memory of the sun setting over the escarpment, for Smith, the title carries an additional metaphorical meaning—a lament for the death of the sacred site, as it became surrounded by suburban development. Smith created The Court House Steps, 1987 in response to the preservation emergency created on September 4, 1987, when a landowner forcibly separated and removed a basalt boulder, marked with petroglyphs, from its site on the escarpment. Using a forklift and truck, he delivered the culturally significant stone to the courthouse steps in protest of the lengthy legal negotiations that were blocking him from building on his private land. The repeating right angles that represent sacred kiva steps in the lower right become high-rise buildings that seem to be growing and tumbling simultaneously in the upper left. Diagonally, across the center of the composition a series of orbs ending in a solar eclipse cast upon yet another set of steps, seem to signify a universe spinning out of alignment.

As Smith worked on the series over time, each painting became a record of her personal as well as political feelings about the landscape of New Mexico. An anomalous painting in the Petroglyph Park series from 1986 is an homage to Georgia O’Keeffe and acknowledges Smith’s respect for American modernism. When O’Keeffe died on March 6, 1986 after having lived in New Mexico since 1949, and worked in the area since 1929, the artist became part of Smith’s narrative. The characteristic petroglyph figures of the series play across the surface of Georgia On My Mind, yet the primary colors and reference to the famous artist in this painting distinguish it from the others in the series. The painting reminds us that Smith’s artwork is always an expression of her life and that in the midst of painting the Petroglyph Park series, O’Keeffe, who had also expressed a very personal connection to the land of New Mexico, was on Smith’s mind.

Smith is a prolific artist, who sometimes sustains a series of more than one hundred works of art—oils, pastel drawings, prints, and mixed media. To demonstrate the breadth of her artistic and political views of the landscape, the 2012 exhibition included works on paper created between 1978 and 1991. Smith’s earliest landscapes from the Wallowa Waterhole Series (1978-1979) express a lyrical, pastoral, and even nostalgic sense of place. The artist credits Paul Klee’s[4] color and composition as the inspiration for the series, which she named for the verdant Oregon valley that was home to Nez Perce Chief Joseph[5] and his people. It was in the interplay of these two disparate influences that Smith first began to create a compelling and complex balance between indigenous traditions and a modernist style. Each pastel drawing in the series can be understood as a personal memory map composed of color fields representing grasslands, flowers, and water, as well as graphic marks that trace travel through the landscape by animals and humans. The later works in the exhibition express a very different sensibility.

In 1989 Smith began a series of landscapes named for Chief Seattle[6], a nineteenth-century leader of the Suquamish and Duwamish people, who is remembered for his eloquent speech of 1854, as he surrendered his people and land to Governor Isaac Stevens. Now recalled as an ecological prophecy, Seattle’s words invoke the spirit of the land and its inseparability from its inhabitants. From that period forward, Smith’s pastels began to visualize the threatened American environment, by creating immediate, beautiful, but menacing images that suggest areas of ruined late-twentieth-century landscape. Smith’s 1991 pastel drawings, no longer reference the romance of a lost paradise. Instead, she generates a new kind of visual tension by applying pastel marks with a sense of raw energy and intensity. The immediacy and anxiety expressed in this body of work set it apart from all of her earlier landscapes.

Although Smith’s landscapes of 1978-91 display a wide range of media and stylistic elements, their overarching theme is the relationship of people to the land they inhabit. As surely as those landscapes deliver her political “messages,” they also establish her as a modernist. Like Georgia O’Keeffe, Jaune Quick-to-See Smith expresses a personal and passionate sense of place that transforms our vision of the American landscape.

The Museum is fortunate to have added Peyote, 1991, a work in the 2012 exhibition, to the Georgia O’Keeffe Museum collection through a generous gift from the artist.

Special thanks to my colleagues Judy Smith, Rana Chan, Dale Kronkright, and Jason Malone as well as Carolyn Kastner for their help on this story!

[1] A petroglyph is an image created by removing part of a rock surface by incising, picking, carving, or abrading, as a form of rock art. Outside North America, scholars often use terms such as “carving”, “engraving”, or other descriptions of the technique to refer to such images. Sourced from Wikipedia, July 2020.

[2] Kate Morris. “Picturing Sovereignty: Landscape in Contemporary Native American Art,” in Painters, Patrons, and Identity: Essays in Native American Art History to Honor J.J. Brody, Joyce M. Szabo, Ed. University of New Mexico Press, 2001.

[3] An escarpment is a steep slope or long cliff that forms as a result of faulting or erosion and separates two relatively level areas having different elevations. Usually, scarp and scarp face are used interchangeably with escarpment. Sourced from Wikipedia, July 2020.

[4] Paul Klee (18 December 1879 – 29 June 1940) was a Swiss-born artist. His highly individual style was influenced by movements in art that included Expressionism, Cubism, and Surrealism. Sourced from Wikipedia, July 2020.

[5] Hin-mah-too-yah-lat-kekt, popularly known as Chief Joseph, Young Joseph, or Joseph the Younger, was a leader of the Wal-lam-wat-kain band of Nez Perce, a Native American tribe of the interior Pacific Northwest region of the United States, in the latter half of the 19th century. Sourced from Wikipedia, July 2020.

[6] Chief Seattle was a Suquamish and Duwamish chief. A leading figure among his people, he pursued a path of accommodation to white settlers, forming a personal relationship with “Doc” Maynard. The city of Seattle, in the U.S. state of Washington, was named after him. Sourced from Wikipedia, July 2020.

~