Rooted In Place

Throughout her life, Georgia O’Keeffe returned over and over to depictions and descriptions of trees, in paintings, sketches, watercolors, and even in her letters. She captured trees in drawings and paintings from her travels around the world and from the places she made home.

Read more information about the trees that fascinated O’Keeffe:

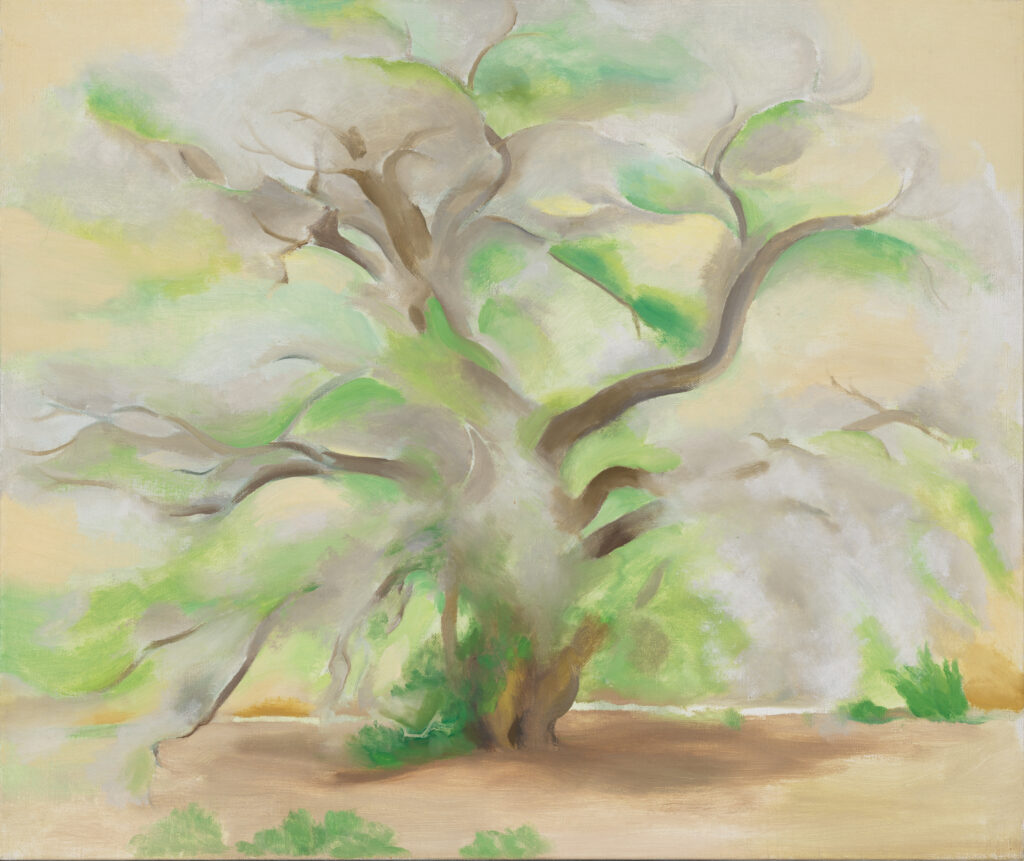

Rio Grande Cottonwood

Populus deltoides subsp. wislizenii

-

Rio Grande cottonwood, botanic name Populus deltoides subsp. wislizenii, is an instantly recognizable icon of the rivers and arroyos of New Mexico. It is a keystone species of the Southwest riparian ecosystem: a keystone species is one which helps define and support an entire ecosystem, without which that ecosystem may drastically change or cease to exist.

Rio Grande cottonwood is the largest native tree in the bosque (pronounced “boh’-skay”), Spanish for “forest,” in local usage the riparian woodland along the Rio Grande and other rivers. One of the largest species in New Mexico, the Rio Grande cottonwood grows to 50-60 feet (15-18 meters) tall, sometimes to 90 feet (27 meters). It grows quickly but does not have a long lifespan, typically around 100 years. It is dependent on a steady water supply but can withstand periods of drought.

This tree is full of life of all sorts. The tall, wide-spreading branches offer shelter and shade to beings from human to hummingbird to honey bee. Smaller trees and other plant species grow in the cottonwood understory, protected from sun and wind by the wide tree canopy. The tree roots help hold riverbanks and sandy riparian soils in place.

Cottonwoods are dioecious, meaning male and female flowers are produced on separate trees. Female trees produce long strings of seeds that ripen and burst open in late spring, the seeds surrounded by the white cottony “summer snow” that gives the tree its common name and that helps the seeds loft on the air, moving to new places.

People have a long connection with this majestic beauty; in fact, the botanic name of Populus (Latin for “the people”) was given to the genus that includes cottonwoods because the leaves fluttering in the wind sound like the pleasant murmurings of a crowd of people.

The cottonwood has many ethnobotanical uses including forage, fuel, and medicine. The light, soft wood is easy to work and is used for fuel, construction, and carving. Trunks have long been used to make large drums. Cottonwoods are in the Salicaceae family, and buds contain salicin, a component used similarly to aspirin.

The Rio Grande cottonwood is one of the last trees to color in the New Mexico autumn. They often produce a spectacular display of gold leaves in October, then drop their leaves to create a layer of organic mulch that protects plants and animals through the cold mountain winters.

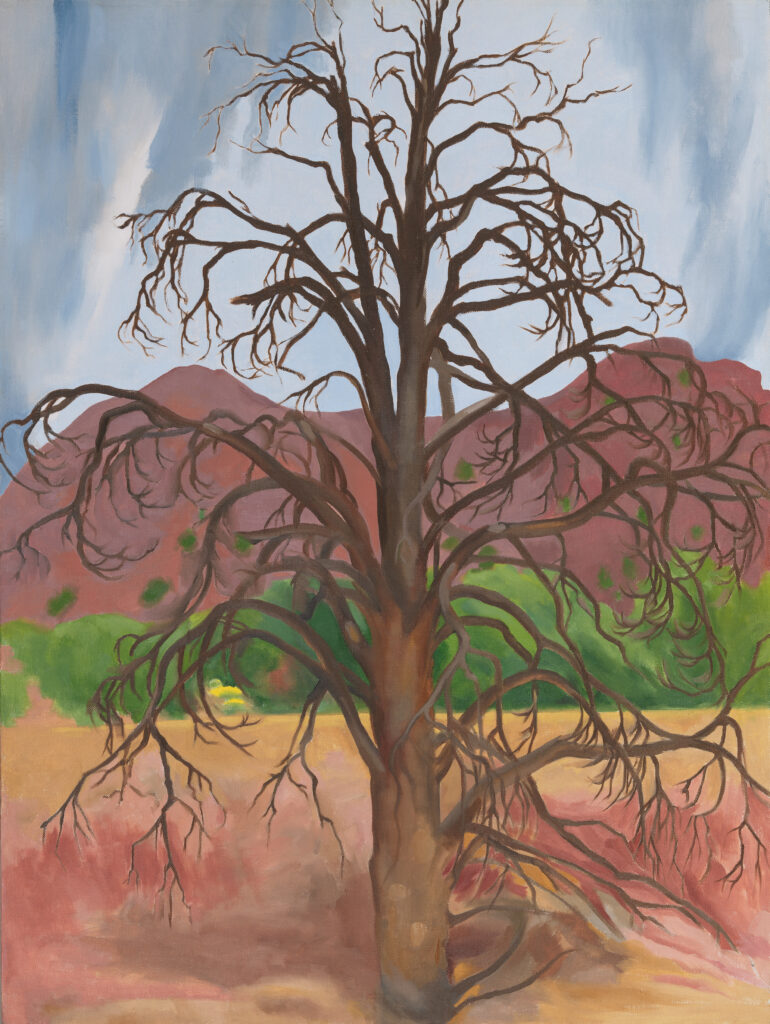

Piñon Pine

Pinus edulis

-

The piñon pine botanic name, meaning “edible pine,” gives a clue to this tree’s importance in the life of the American west. This pine produces high-fat seeds (“pine nuts”) that may be the most nutrient dense plant food source in the Southwest. These seeds have long formed an important part of the diet of innumerable humans, birds, mammals and other life forms.

Piñon pine is a keystone species in its native woodland, providing shade, shelter, protection, erosion control and numerous other services to the ecosystem, along with the densely nutritious seeds.

Piñons can live several centuries, up to 1,000 years, with mature trees being especially valuable in the forest. Trees start bearing cones around age 25, with maximum seed production at ages 50-200 years. Cones take 2-3 years to mature, and trees typically set few to no cones during drought years.

The wood, bark, needles and seeds have been used for digging sticks, arrow shafts, weaving tools, house-building materials, food, medicine and as fuel for heating, cooking, and firing pottery for at least 10,000 years. They continue to be harvested and utilized today.

Piñon pine can grow 10-30 feet (3-9 meters) tall. It has a rounded, bushy appearance, often with multiple trunks and wide horizontal branches. It can tolerate drought thanks to an extensive root system that can extend deep into the soil and more than twice the radius of the tree canopy, although most roots are within the top 16” (40 cm) of soil. The roots associate with mycorrhizal fungi which help the tree obtain water and nutrients from an even greater soil area. Trees that have withstood drought and other stresses may lose large branches or even trunks, walling off damaged areas so the rest of the tree may live, resulting in gnarled, sculptural shapes.Extended drought such as we’ve experienced in the American southwest since about the year 2000 is a primary threat to the health and life of piñon pines. Drought-stressed trees succumb more easily to threats by piñon-needle scale, pine bark beetle, and various diseases. Biologists studying forest systems and plants in the American west predict that piñon pine numbers will likely decrease steadily in the next several decades as warmer temperatures and drought exacerbated by climate change take their toll.

Piñons and junipers grow in similar conditions and are often found together in woodlands. Piñon-juniper woodlands, with the exact mix of these two trees varying with altitude, precipitation, and other variables, are the most common forest type in the American Southwest.

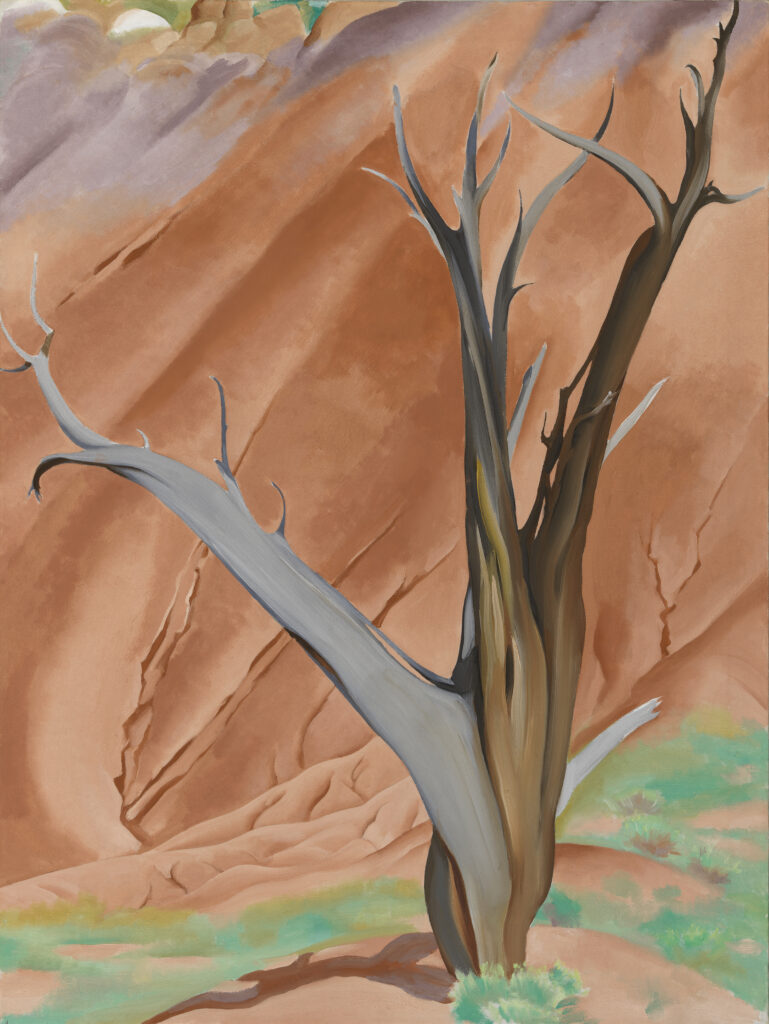

One-seed Juniper

Juniperus monosperma

-

One-seed Juniper is the ubiquitous small evergreen tree of the windy savannahs and dry foothills of the American West, at elevations from 3,000 to 7,500 feet (900-2,300m).

Like piñon pine, its fruits provide food for many species. The small blue fleshy cone with a waxy appearance, often called “berry,” contains one hard seed. It is less fatty and nutritious than the piñon pine seed, but is perhaps an even more important survival food for many animals. The juniper cones mature in one season, and junipers can tolerate more heat and drought than piñon pines, so are more likely to produce seed in dry years.

Junipers are dioecious, with male and female productive parts on separate plants. Female plants begin producing the cones from approximately age 10-30 years; males produce abundant pollen which flies to female plants on the wind.

One-seed juniper can grow to 20-25 feet (6-8 m) but is more often seen in the 12-15 foot (3.5-4.5 m) range. It is a very shrubby, usually multi-trunked conifer, with scale-like needles more yellow-green than the bluer green of piñon needles.

Human uses of juniper include all the usual uses for native trees: wood for fuel and construction; bark and leaves for forage; various parts of the tree for medicine. Juniper wood is rot resistant which makes it especially useful for fence posts and tools. Humans have used the juniper seeds for medicine, flavoring, and sometimes food. The resinous seed cones become much sweeter after a few autumn freezes.

Juniper is resilient and durable. Its roots go far deeper than other similar-sized trees such as piñon pines, so the trees are able to bring water up from deep in the soil. They also resist cavitation—a break in the water column that brings water up from roots to leaves– better than many other trees, including piñon. However, in extended droughts junipers may grow extremely slowly or even cease growth for a time.

Even dead trees are important components in the ecosystem. Birds and mammals of many sizes and habits use the standing trees for nesting and raising young. The roots continue to hold fragile soils against erosion. Fallen trees create pockets of moisture and shade to help other plant species germinate and grow, and the decomposing wood and roots nourish important soil microorganisms and support insect life.

During the 20th century junipers were often cut, burned, or otherwise eradicated from hundreds of thousands of acres of grasslands and other areas as they were considered weed trees that took resources from other more valuable plants. We are now learning that they are a keystone species and vitally important in a number of ecosystems, especially in lands where very few tree species thrive at all.

A local entomologist studied the one-seed junipers on her property and discovered that over 450 insect and arachnid species lived in or on the tree over a year. This alone tells the wealth of life that the juniper supports, when you consider how many animals up the food chain, and decomposers further down, live on tiny 6- and 8-legged invertebrates.

—

Rooted in Place offers a collection of Georgia O’Keeffe’s studies of trees, from the piñon and cottonwoods near her homes in New Mexico, to maples at Lake George and palm trees in the Caribbean. This exhibition was created in partnership with the Santa Fe Botanical Garden to include further information about the botanical nature of a subject that caught O’Keeffe’s fascination again and again.