O’Keeffe’s Letters From India

In the spring of 1959, Georgia O’Keeffe spent almost four months in Asia.

During that time, she wrote her sister, Anita Young, a handful of letters describing the countries she visited and the “astonishing things” she saw. These letters form a small part of the thousands of pages that make up O’Keeffe’s literary legacy. Though best known for her visual art and her ability to allow “us to experience the nonobjective as mystical, familiar, objective and subjective all at once,” to be simultaneously objective and subjective, O’Keeffe’s literary art adheres to many of the same tenets of modernism. Elemental, spare, and full of the kinds of voids that punctuate her art, they are fearless explorations of the world around her. “Tonight I’d like to paint the world with a broom,” she writes. And, “There is so much color in the cliffs one doesn’t think to look for the sunset.”

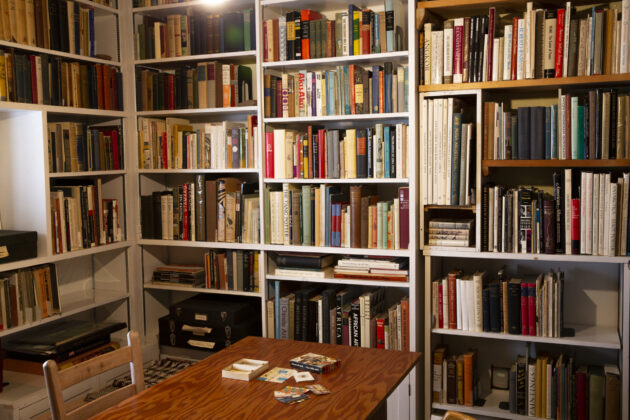

For the past five years, I been reading and studying O’Keeffe’s letters as I complete a book, Letters Like the Day: Essays Inspired by the Literary Art of Georgia O’Keeffe. A generous fellowship from the Georgia O’Keeffe Museum Research Center brought me to Santa Fe this past spring so that I could complete this project. In this essay, I explore the letters O’Keeffe wrote from Asia in order to provide a brief example of the rewards found in pairing her visual and literary arts. By the time O’Keeffe left for Asia in the spring of 1959, she was already a world traveler. South America, Mexico, and Europe were behind her. Still, in 1959, traveling within India was no easy feat, even as part of a tour group. O’Keeffe prepared for her trip, reading up on how to dress for the heat and the culture, how to prepare food and water, and how to mail letters home. She had spent years intrigued by Eastern religions. Both her Ghost Ranch and Abiquiu libraries are full of books describing Eastern art, architecture, philosophy, and practices. Specific books, such as Stella Kramrisch’s The Art of India (Phaidon, 1954, are festooned with bits of paper marking artworks she wanted to or did see while abroad. By the time she boarded her plane in Albuquerque, O’Keeffe was as ready as she could be to visit the other side of the planet.

In her first letter home from Japan, O’Keeffe begins writing on a theme that runs throughout her trip—in fact, a theme she carried throughout her life: the desire and the inability to fully capture the world around her. In a letter begun February 1, 1959, she starts to describe the temples and shrines, the climb up the mountains to reach them, but concludes that “they were wonderful in a way that is very difficult to explain.” Later in the letter, having visited a Zen temple with a room for meditation and a stone garden, she adds, “The good things are so good one just can’t tell about them.”

Though O’Keeffe’s letters are filled with lyrical language and stunning details, she just as frequently asserts that what she is seeing and experiencing is impossible to put into words. In fact, she makes clear her distrust of language. “Words have been misused,” she once wrote to Derek Bok, the then-president of Harvard. “The usual words don’t express my meaning and I can’t make up new ones for it.” In her early correspondence with Alfred Stieglitz she was even more direct: “Words and I–are not good friends.” Her vocabulary was pigment. “I paint,” she once said, “because color is a significant language to me.”

For O’Keeffe, though, to admit that she can’t address her experience fully on the page alerts the reader to the fact that she has entered the very kind of space that propelled her art. O’Keeffe loved to have her world turned upside down. The plains of West Texas, a barren landscape most would avoid, inspired her because of their very emptiness. In an early letter to Stieglitz about this landscape, she writes: “More–I want–to say–but what–.” After that dash–the mark of punctuation that opens a syntactical void on the page–she continues, “I guess that space is between what they call heaven and earth–out there in what they call the night–is as much it as anything.” It is the “it” found in emptiness, the inexplicability of seeing, that she pursued on her canvases. And the approach to the “it” is often signaled in her letters by dashes, white space, and grieving the gap between experience and words.

Her frustrations with language and her proximity to the ineffable only increase when O’Keeffe leaves Japan and arrives in India. Half of her time in Asia is dedicated to India, and the number of postcards and booklets she collects and carries home make clear that India moves her most strongly. Almost before she sets foot in the country, she understands that what she will experience there will change her. Here is the second sentence she posted from India: “It seems that as we go on more and more what I see is hard to tell about.”

India is complicated in a way that the rest of O’Keeffe’s travels are not. She visits the site in Varanasi where the Buddha gave his first sermon, and climbs to mountain stupas to share tea with Tibetan monks (“I feel I have been on top of the world”), but she also faces the crowded streets, the poverty, and the heartache: “All these places are dirty and crowded–people dressed in white that seems never to be washed.” In Varanasi, she adds, “there were harrowing sights in the streets,” but, she tells her sister, she just learned not to “look at it.”

O’Keeffe gives no more detail about what she witnessed. Having traveled in India, I imagine she faced men without limbs and children without mothers, as well as the heartbreak that happens when the number of outstretched palms far exceeds the rupees one has to give. The press of such need, combined with the cacophony of sounds, scents, and colors, overwhelms. But with the difficulty arrives great beauty. O’Keeffe writes, in a postcard to her friend Maria Chabot, “It is a kind of world one cannot believe is true. The largest temples we have seen just left me speechless–It is really devastating.” Both beauty and pain devastate her, as does the art she sees; the paintings, the statues, the carvings: a standing Buddha that provides “the finest depiction of the dignity of man that I have ever seen”; a religious festival that is “the most spectacular thing I ever saw”; a god carried on a cart. She writes to Anita, “The religious feeling that is everywhere is all something warm that we just don’t have–the eyes that meet you are gentle.” By the time she reaches Bombay, from where she will visit the luminous cave carvings in Ajanta and Ellora, she has begun to set the blissful and the difficult side by side. She tells Anita about riding on an elephant to a fort. “Elephant riding is a little rough and the sun a bit hot but it goes with India I suppose.”

It is after her time at the caves, toward the end of her travels in India, that O’Keeffe begins to articulate just how much her world has shifted. And perhaps that makes perfect sense, given the message articulated by the stone carvings at the Ellora and Ajanta caves, which simultaneously celebrate Hinduism, Buddhism, and Jainism: that disparate ideas are not to be held in tension but can actually point to the one reality. She writes that her time at the caves has given her “startling experiences . . . that shift my ways of thinking about many things.” Just which “things” have shifted we are once again left to guess, but one of her last letters home to Anita provides a clue.

In the final long letter she posts home, O’Keeffe tells Anita, “I must speak to you this morning . . . such things I have seen out the window I have never dreamed—this is more like my dreams than anything I have ever seen.” She is specifically writing of the rivers below the plane as she flies, but one gets the sense that she is describing her entire time in Asia. She continues, “I really can’t tell of it but it makes me believe in my dreams more than I ever have.”

To fully understand the significance of these lines, it helps to return to O’Keeffe’s early struggles to realize her own artistic vision. In the well-known story, O’Keeffe, living in Columbia, South Carolina, worked in the fall of 1915 to move away from what had already been done in visual art and to find her own way of seeing. She sat on the floor of her room with paper around her and only charcoal in her hand, and she stayed there until she broke through. Of course, what waited for her on the other side of those long, lonely nights were the pure forms of abstraction, some of the first in the world. They were unlike anything that had ever been done, and they came from some deep, inarticulate place inside her. She was unsure of what she had. She wrote, to her friend Anita Pollitzer, “I wonder if I am a raving lunatic for trying to make these things.” When she shared these early drawings with Stieglitz, she told him the drawings were a way “to express myself–things I feel and want to say–haven’t words for–You probably know without my saying it–that I ask because I wonder if I got over to anyone what I want to say.”

That was the value of abstraction for O’Keeffe: its ability to translate consciousness itself, to “get over” to another what words cannot contain. And what she found in India in the spring of 1959–the poverty, the carvings, the gentle eyes, the unbelievable wonder of it all–resonated with O’Keeffe on the deepest of levels. They were, in fact, her dreams made manifest.

It should come as no surprise, then, that when O’Keeffe returned from India, she produced some of the purest abstractions of her career, paintings that seem reminiscent of her early work in their approach to line and form. But this was not a return. It was a continuation of a journey begun decades before–a journey that can be traced in her words as well as in her art, and that startles us as much now as it must then have startled her.

Notes

Unless otherwise noted, all letters cited here can be found in the Alfred Stieglitz/ Georgia O’Keeffe Archive, Yale Collection of American Literature, Beinecke Rare Book and Manuscript Library, Yale University.

“Astonishing things,” Georgia O’Keeffe (GOK) to Anita Young (AY), April 13, 1959. “Us to experience the nonobjective.” “Does the New Whitney Show That Modernism Never Really Happened in America?” Jerry Saltz and David Wallace- Wells. http://www.vulture.com/2015/05/saltz-did-modernism-even-happen-in- america.html. Accessed August 14, 2105.

“Tonight I’d like,” GOK to Alfred Stieglitz (AS), November 4, 1916. “There is so much color,” GOK to AS, August 27, 1934. “They were wonderful,” GOK to AY, February 11, 1959. “Words have been misused,” GOK to Derek Bok, June 1973. Jack Cowart, Juan Hamilton, Sarah Greenough, eds., Georgia O’Keeffe: Art and Letters (New York Graphic Society, 1990), 270.

“Words and I,” GOK to AS, February 1, 1916. “I paint because,” Karen Karbo, How Georgia Became O’Keeffe: Lessons on the Art of Living (Guilford, CT: Globe Pequot Press, 2012), 117. “More—I want—,” GOK to AS, March 15, 1917. “It seems that,” GOK to AY, March 15, 1959. “I have been on top,” GOK to AY, March 15, 1959. “All these places are dirty,” GOK to AY, March 15, 1959. “There were harrowing,” GOK to AY, March 15, 1959. “It is a kind,” GOK to Maria Chabot, March 4, 1959. Georgia O’Keeffe Museum Research Center Archives: Letters to AS, 1933–1944, undated. “The finest depiction,” GOK to AY, March 23, 1959. “The most spectacular,” GOK to AS, April 13, 1959. “The religious feeling,” GOK to AY, March 15, 1959. “Elephant riding,” GOK to AY, April 13, 1959. “Startling experiences,” GOK to AY, April 13, 1959. “I must speak to you,” GOK to AY, April 25, 1959. “I wonder if I am a raving,” GOK to Anita Pollitzer, December 1915. Clive Giboire, ed., Lovingly, Georgia: The Complete Correspondence of Georgia O’Keeffe and Anita Pollitzer (New York: Touchstone Books, 1990), 103. “To express myself,” GOK to AS, January–May 1916. Sarah Greenough, ed., in her My Faraway One: Selected Letters of Georgia O’Keeffe and Alfred Stieglitz, Volume 1, 1915–1933 (New Haven, CT: Yale University Press, 2011), dates this letter early January 1916.

From April through June 2015, Jennifer Sinor was in residence at the Georgia O’Keeffe Museum Research Center for a three-month fellowship as she worked on a book project titled Letters Like the Day: Essays Inspired by the Literary Art of Georgia O’Keeffe—a collection of lyric pieces exploring and responding to O’Keeffe’s letters as literary art. Dr. Sinor is a Professor of English at Utah State University, where she teaches creative writing. Samples of her published essays and a list of the awards she has won can be found at her website, jennifersinor.com.

This article was written by Jennifer Sinor