Charlotte Perkins Gilman and Forerunner

From the Bookworm: Georgia O’Keeffe and Charlotte Perkins Gilman

I was familiar with the writer Charlotte Perkins Gilman because of a women’s literature class I took in college. We read Gilman’s “The Yellow Wallpaper”, and though I have never been much of a fiction reader, the feminist narrative connected with my own growing feminist thoughts. I also knew of, but never read, Gilman’s feminist utopian novel Herland. However, I didn’t learn about the breadth of Gilman’s poetry, fiction and nonfiction writings until I cataloged Georgia O’Keeffe’s copy of Gilman’s self-published feminist magazine Forerunner.[1] And, it wasn’t until I decided to write about this item from O’Keeffe’s personal library, that I learned what many folks already knew and have written about Gilman: her feminism, like much of first-wave feminism[2] was tied to racism and eugenics.

Georgia O’Keeffe, Forerunner and “The Dress of Women”

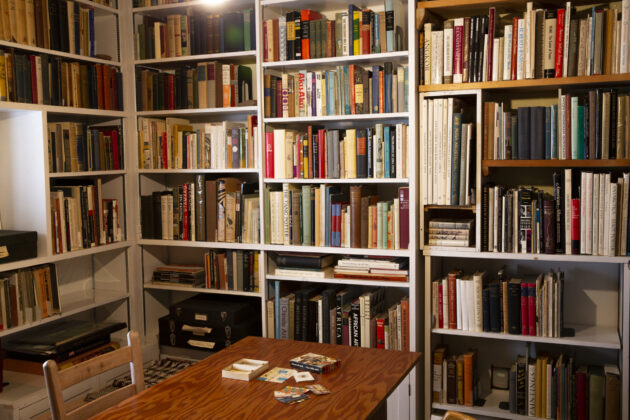

In 1916, while O’Keeffe was living in Canyon, Texas, she wrote to her friend, suffragist Anita Pollitzer[3] about Charlotte Perkins Gilman and Forerunner: “Do you ever read the Forerunner? I remember asking you last year – It isn’t going to be published after December – but Ive been having a great time with the 1915 volume. There is an article “The Dress of Women” in it that is great – She is certainly a sweet old girl.” ‘She’ refers to Charlotte Perkins [Gilman] – the woman who writes and publishes it.[4] O’Keeffe kept the 1915 issue of Forerunner in her Abiquiú Bookroom[5]. She inscribed her copy with her name and date; something she didn’t usually do in her books, this was more a habit of her husband’s, Alfred Stieglitz. O’Keeffe copied Carl Sandburg poems inside the front cover and on the front loose endpaper. Sandburg’s first poetry publication, Chicago Poems, was published in 1916 and O’Keeffe made note of it on Forerunner’s front loose endpaper. A copy of Sandburg’s book[6] is also held in O’Keeffe’s library; that particular copy is inscribed by Sandburg to Stieglitz, reminding me that O’Keeffe’s libraries[7] offer an endless number of research possibilities.

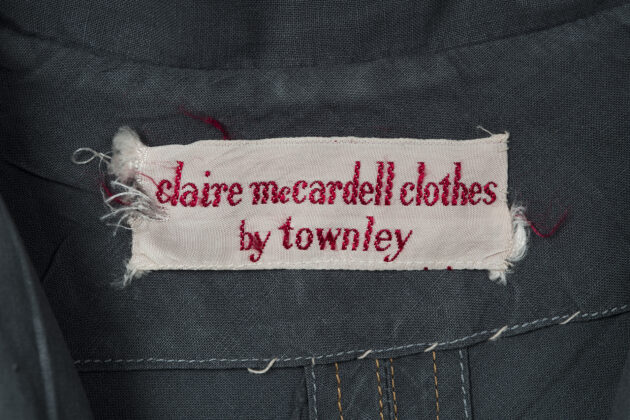

O’Keeffe’s primary interest in Forerunner was in the serialized essay, “The Dress of Women”, where she marked several passages. In “The Dress of Women”, Gilman “analyzes the social, cultural, economic, and psychic meanings of women’s dress, focusing on the ways in which it “impede[s] the social development of the wearer.”[8] In another 1916 letter to Pollitzer, O’Keeffe wrote about the essay, “Its absurd – I sit here trying to think what I’ve read-and-I-don’t know-it seems that it has been poetry-but I dont know”.[9] “The Dress of Women” likely had a profound influence on O’Keeffe, and as noted by scholar Linda Grasso, “Gilman’s combination of logic, analysis, and advice offered her a perspective, a way of thinking, and a blueprint for sartorial self-fashioning.”[10] Wanda Corn explores O’Keeffe’s clothing aesthetic in great detail in the catalog for the wildly popular exhibition, Living Modern. Accordingly to Corn, “While O’Keeffe never said exactly what she responded to in Gilman’s forceful essays…She would also have agreed with Gilman’s ferocious critique of current women’s fashions, railing against hobble skirts that made it difficult for women to walk, or costumes that fastened in the back and required a woman, like a child, to get help dressing.”[11]

While O’Keeffe’s interest in Gilman seems relegated to Gilman’s theories on dress, it is necessary to place Gilman in context, or at the very least call attention to, the theories of eugenics and racism in her feminist ideologies. And, though I don’t intend on unpacking feminist theories or histories here, it should be noted that much of the first-wave feminist movement was connected to racist ideologies, and that genealogy of racism has been a continued thread throughout the different waves of mainstream white feminism.[12]

Charlotte Perkins Gilman’s Feminism

Charlotte Perkins Gilman (1860-1935) was an influential white feminist, social reformer, suffragist, lecturer and writer. Among her most well-known works is the short story “The Yellow Wallpaper” (1892), the feminist utopian novel Herland (1915) and Women and Economics (1898). Gilman is often remembered for her utopian narratives and views on women’s economic dependence. What is obscured in simplified feminist readings on Gilman is her dedication to a feminism rooted in eugenicist thinking and white supremacy. Eugenics is the selection of desired heritable characteristics in order to improve future generations, typically in reference to humans, and postulates the dangerous idea that some humans are biologically superior to others.[13] It is important to note the prevalence of these ideas and beliefs in mainstream white feminism, and generally, in Gilman’s era and beyond. Several writers explore Gilman’s eugenics theories both in her nonfiction and fiction works. A selected list of additional articles and websites can be found below. As pointed out by Asha Nadkarni’s in the publication Eugenic Feminism:

Although Gilman was one of the most influential and prolific feminist scholars of her time, her work fell into obscurity until it was rediscovered in the 1960s and 1970s. The Gilman revival began with the 1968 reprint of Women and Economics, the 1973 reprint of “The Yellow Wallpaper,” and the 1979 reprint of Herland….And yet, as critics such as Alys Eve Weinbaum and others have argued, feminist celebrations of Gilman’s work overlook the artiuclaiton of feminism to racism both in Gilman’s time and our own.”[14]

Closing Thoughts

What did O’Keeffe think about Gilman’s theories on race? I’m not sure; I didn’t find any evidence by way of O’Keeffe marking passages, or writing her thoughts to other people. Not calling attention to a wider picture of Gilman’s theories obscures her dedication to, support of, and participation in a feminism rooted in eugenicist thinking and white supremacy. In merely calling attention to this, I hope to help foster a more complex dialogue about O’Keeffe, the times in which she lived, and the complexities of the materials held in the Museum’s collections.

Additional Resources

About Charlotte Perkins Gilman

“Charlotte Perkins Gilman.” 2013. Radcliffe Institute for Advanced Study at Harvard University. October 2, 2013. https://www.radcliffe.harvard.edu/schlesinger-library/collection/charlotte-perkins-gilman.

Website Dedicated to Charlotte Perkins Gilman https://www.charlotteperkinsgilman.com/.

“Charlotte Perkins Gilman Digital Collection.” Schlesinger Library Online Digital Collections. Accessed September 11, 2020. http://schlesinger.radcliffe.harvard.edu/onlinecollections/gilman/.

“Herland: The Forgotten Feminist Classic about a Civilisation without Men.” 2015. The Guardian. March 30, 2015. http://www.theguardian.com/lifeandstyle/2015/mar/30/herland-forgotten-feminist-classic-about-civilisation-without-men.

Bolick, Kate. 2019. “The Equivocal Legacy of Charlotte Perkins Gilman.” The New York Review of Books (blog). April 1, 2019. https://www.nybooks.com/daily/2019/04/01/the-equivocal-legacy-of-charlotte-perkins-gilman/.

Critical Articles on Charlotte Perkins Gilman

Knight, Denise D. 2000. “Charlotte Perkins Gilman and the Shadow of Racism.” American Literary Realism 32 (2): 159–69. http://www.jstor.com/stable/27746975

Lanser, Susan S. 1989. “Feminist Criticism, ‘The Yellow Wallpaper,’ and the Politics of Color in America.” Feminist Studies 15 (3): 415–41. https://doi.org/10.2307/3177938.

NadKarni, Asha. “Perfecting Feminism: Charlotte Perkins Gilman’s Eugenic Utopias.” In Eugenic Feminism: Reproductive Nationalism in the United States and India, 33-64. Minneapolis; London: University of Minnesota Press, 2014. Accessed September 11, 2020. http://www.jstor.org/stable/10.5749/j.ctt6wr7s6.4.

Seitler, Dana. 2003. “Unnatural Selection: Mothers, Eugenic Feminism, and Charlotte Perkins Gilman’s Regeneration Narratives.” American Quarterly 55 (1): 61–88. https://www.jstor.org/stable/30041957

Weinbaum, Alys Eve. 2001. “Writing Feminist Genealogy: Charlotte Perkins Gilman, Racial Nationalism, and the Reproduction of Maternalist Feminism.” Feminist Studies 27 (2): 271–302. https://doi.org/10.2307/3178758.

End Notes

[1] Gilman, Charlotte Perkins. Forerunner: a Monthly Magazine. New York: The Charlton Company, 1909-1916. https://library.okeeffemuseum.org/cgi-bin/koha/opac-detail.pl?biblionumber=10437 View a copy online: https://babel.hathitrust.org/cgi/pt?id=mdp.39015029837609&view=1up&seq=7

[2] “The Waves of Feminism, and Why People Keep Fighting over Them, Explained – Vox.” n.d. Accessed September 11, 2020. https://www.vox.com/2018/3/20/16955588/feminism-waves-explained-first-second-third-fourth.

[3] Pollitzer, Patty. n.d. “Anita Pollitzer (U.S. National Park Service).” National Park Service. Accessed September 11, 2020. https://www.nps.gov/people/anita-pollitzer.htm.

[4] “Letter from Georgia O’Keeffe to Anita Pollitzer, October 30, 1916.” 1990. In Lovingly, Georgia : The Complete Correspondence of Georgia O’Keeffe & Anita Pollitzler. New York: Simon & Schuster Inc.

https://library.okeeffemuseum.org/cgi-bin/koha/opac-detail.pl?biblionumber=317

[5] “Abiquiu Bookroom – Georgia O’Keeffe’s Personal Libraries – Engl Library & Archive at Georgia O’Keeffe Museum.” n.d. Accessed September 11, 2020. https://okeeffemuseum.libguides.com/guides/okeeffe-libraries/abiquiu.

[6] Sandburg, Carl. Chicago Poems. 1st ed. New York: Henry Holt and Co., 1916. https://library.okeeffemuseum.org/cgi-bin/koha/opac-detail.pl?biblionumber=9389

[7] “Engl Library & Archive: Georgia O’Keeffe’s Personal Libraries: About.” Accessed September 11, 2020. https://okeeffemuseum.libguides.com/guides/okeeffe-libraries/about.

[8] Grasso, Linda. Equal under the Sky : Georgia O’Keeffe and Twentieth-Century Feminism. Albuquerque: University of New Mexico Press, 2017, 61.

[9] “Letter from Georgia O’Keeffe to Anita Pollitzer, November 1916.” In Lovingly, Georgia : The Complete Correspondence of Georgia O’Keeffe & Anita Pollitzer. New York: Simon & Schuster Inc., 1990.

[10] Grasso (2017, 63-64)

[11] Corn (2017, 43)

[12] For an introduction to racism in feminism: “Race And Feminism: Women’s March Recalls The Touchy History.” n.d. NPR.Org. Accessed September 11, 2020. https://www.npr.org/sections/codeswitch/2017/01/21/510859909/race-and-feminism-womens-march-recalls-the-touchy-history. “The Suffragettes Were Not Allies to Black Women, They Were Racist.” 2019. Education Post. August 24, 2019. https://educationpost.org/the-suffragettes-were-not-allies-to-black-women-they-were-racist/. “Feminism and Inclusion | White Supremacy to Colorblindness.” March 8, 2019. YWCA Southeast Wisconsin. Accessed September 23, 2020. https://www.ywcasew.org/blog/2019/03/08/feminism-and-inclusion-white-supremacy-to-colorblindness/

[13] Eugenics, the selection of desired heritable characteristics in order to improve future generations, typically in reference to humans. The term eugenics was coined in 1883 by British explorer and natural scientist Francis Galton, who, influenced by Charles Darwin’s theory of natural selection, advocated a system that would allow “the more suitable races or strains of blood a better chance of prevailing speedily over the less suitable.” Brittanica. Accessed September 23, 2020. https://www.britannica.com/science/eugenics-genetics

[14] Nadkarni, Asha. Eugenic Feminism: Reproductive Nationalism in the United States and India. Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press, 2014, 33.

Featured image: Unknown. Georgia O’Keeffe in Canyon, Texas, Circa 1916. Gelatin silver print, 3 7/8 x 3 1/16 inches. Georgia O’Keeffe Museum. Gift of The Georgia O’Keeffe Foundation. [2006.6.724]